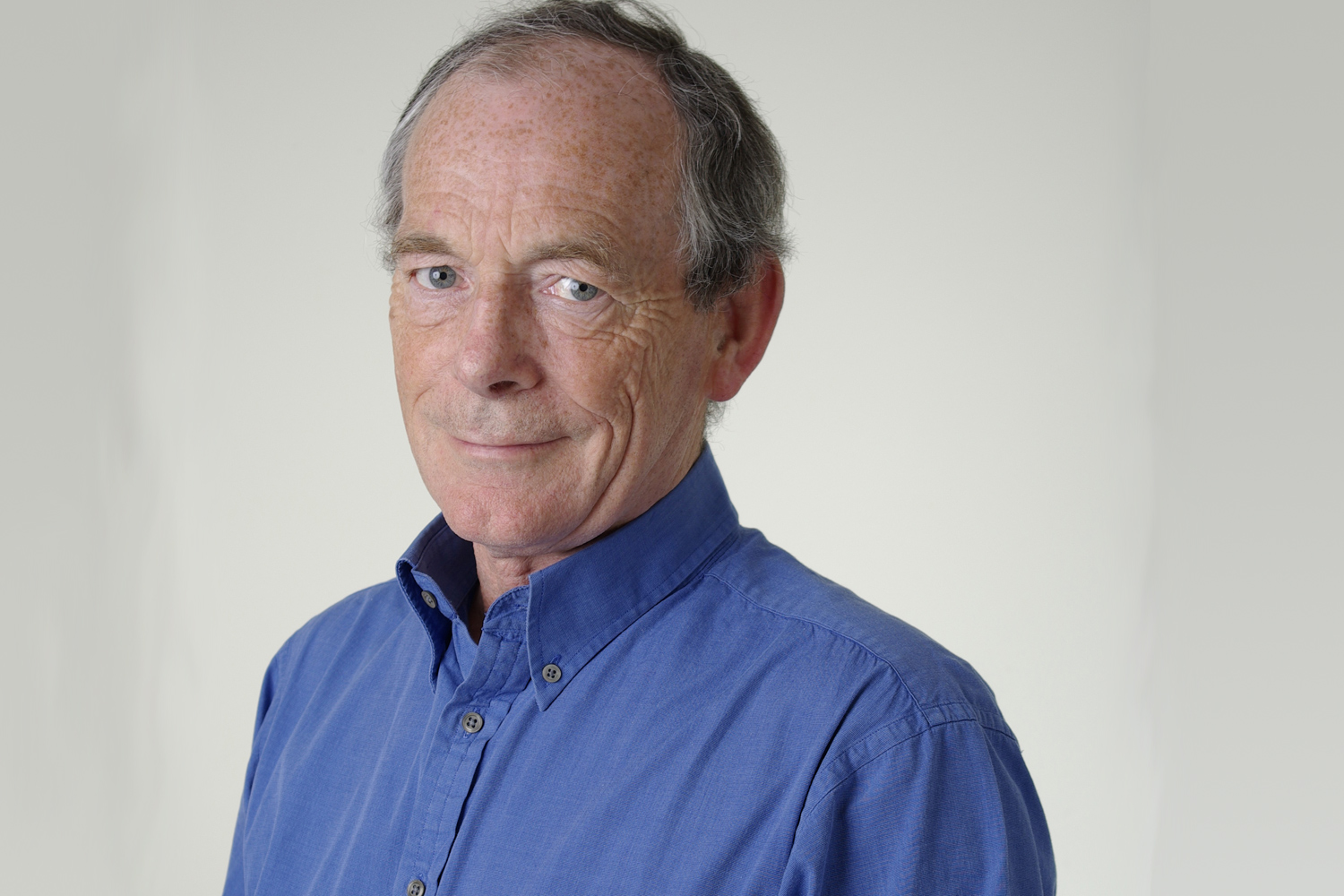

This is Brexit poker – and Theresa May was right to up the stakes

Simon Jenkins

It was strategically sensible to begin the skirmishes in uncompromising mood. The inevitable compromises will come later

The siege of Harfleur was a disaster for the English. Henry V was humiliated and had to abandon his march on Paris, turning instead to confront the French cavalry at Agincourt. Here he faced overwhelming odds but decided to rely on bluff, cunning and Welsh archers to rescue a shred of glory from his European venture.

Theresa May must hope she is somewhere between Harfleur and Agincourt. She is embarked on a seemingly life or death project, its outcome wholly unpredictable. It was not of her making, but that of David Cameron and the British electorate. She has two months to go to invoking article 50, at which point she will find herself between 27 European Union devils and the deep blue sea. Small wonder that on Tuesday she decided on bravado and Shakespeare, goading her ministers “like greyhounds in the slips, straining upon the start. The game’s afoot.”

In setting out the terms of engagement, May had no option but to hang tough. That is what her EU opposite numbers have been doing for six months of virtual denial of Brexit. Much of Brussels still does not believe it will happen, while Europe’s elected politicians at least sense that anti-EU sentiment is growing in their backyards. There are stirrings of a peasants’ revolt, with votes for pitchforks. The last thing they want is a crowing, preening British leader seeking “to have my cake and eat it”. Hence their cursory treatment of May in her few EU encounters so far. To them, she is toxic.

That is why the prime minister clearly felt the need to lay the revolver of “hard Brexit” on the table, to tell the Brexit deniers that Britain would be just fine on the deep blue sea. She threatened them with a trade war and fiscal blitzkrieg. She threatened an offshore Singapore, a Grand Cayman, a 51st state of America, a thousand City traders unleashed on Europe’s banks if “passporting” is denied. Much of this was bravado, but jingoism was the tactic of the moment.

There is no way Brexit can avoid going “soft” in the course of negotiation. As the veteran historian David Marquand said last week, Britain is “part” of Europe in so many ways that amputation is not an option. But there are reckless forces behind hard Brexit, on the right in Britain and among EU finance houses that might benefit from it. The fanciful timetables in May’s speech, notably on trade, may serve to spur her troops into battle, but the spectre is not of hard or soft Brexit but of shambles.

Behind the poker table bluff is realism. The prime minister has already indicated flexibility on migration, on which topic all Europe, left and right, is in a state of panic. She regards membership of the single market, even of a customs union, as going beyond her referendum mandate. But she still wants a “comprehensive, bold and ambitious trade agreement”, something called “associate membership of the customs union”. This sounds like a one-sided Platonic affair, which is nonsense. And it will soon have to be resolved.

Britain will need to avoid a “cliff edge” in two years’ time on matters such as finance, fishing and agriculture. This means markets that may require British payments to join. It may mean European court judgments Britain will have to accept. May knows this. Nor is it realistic to rely on a deal with Donald Trump as substitute for open trade with Europe. Britain will need some association with the EU. Beyond that platitude, all is up for grabs.

The reaction of Europe’s leaders to May’s speech was significant. Most welcomed a sight of even vague red lines. The EU’s Donald Tusk acknowledged her speech as “realistic” and “pragmatic”. The official response from the president, Jean-Claude Juncker, was full of bland words such as fairness, respect and hope for “good results”.

The chief EU negotiator, Guy Verhofstadt, warned against cherry-picking, but it depends which cherries he is talking about. Picking cherries is precisely what May feels she has been told to do. If she gets none, the British people will eat their own. But deals there will be, slithering backwards from hard towards soft, not as far as the single market, towards what I imagine will be called an “accommodation”. Wheels are starting to turn. Money talks.

Commentators pretend to clairvoyance. They supposedly come unencumbered by prejudice or tribe, confronting the options of those in power with fierce scepticism. They can seem glib. But I have never thought politics easy. Elected politicians must forever wrestle with “the crooked timber of mankind”. For them to succeed is rare, to fail normal. I admire them for it.

In that light, I cannot recall a tougher peacetime task for a modern politician than now faces Theresa May. Europe had blighted British leaders for six centuries or more. The most successful, such as Elizabeth I, Walpole, Pitt the Elder, Gladstone and Salisbury, struggled to avoid its snares and were stronger for it. The EU ultimately wrecked three recent prime ministers – Margaret Thatcher, John Major and David Cameron. It would have done the same to Tony Blair if Gordon Brown had not saved him from the euro.

Membership of the EU was never necessary to British prosperity. The country’s overall trade in goods with the EU is not large, and the much larger trade in services is mostly unregulated by Brussels. Britain could survive hard Brexit, and if some of the gilt is shaken off the flatulent City of London it might be no bad thing.

The politics of Europe are a different matter. They have always been fragile, and are more so today than for a long time. I voted to remain in the EU because the eurozone is a disaster and Germany needed an active British presence to help rescue Europe from this ghastly mistake. The threat to Europe is not of war but of nastiness, of a fractious turning in of states on themselves and degenerating into poverty and anti-German hostility. Europe needs Britain’s diplomatic engagement never more than now.

For all the drum-banging, May’s performance on Tuesday was not unfriendly to Europe. It was the first sign she has shown of coherent leadership. No one – I doubt if even the prime minister – can know where this leadership is heading. That is the curse, and the glory, of referendums.